by Lisa Graziano, M.A., LMFT

Most children and adults with PWS are highly motivated to have friends, but for most, friendships don’t come easily, if at all. More often than not, our loved ones don’t quite fit squarely into the Special Needs World, nor do they fit entirely in the Typical World. Our loved ones often live with one foot in each world; constantly, precariously straddling and balancing both. This balancing act expends a lot of energy.

At first glance, social media looks to be an excellent way for persons with PWS to connect with and enjoy the company of others. Whether through Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, Snapchat, or TikTok, reachable by computers, smart phones, and gaming systems, some platform is always readily available for our loved one to connect, share, and interact with someone in some virtual community somewhere in the world.

The challenge is that most kids and adults with PWS lack the skills required to use social media responsibly and safely. Let’s first look at why this is true and then let’s look at what it takes for them to engage appropriately on some social media platforms.

How does PWS interfere with using social media appropriately?

To varying degrees, PWS interferes with executive functioning skills and social functioning skills. The loss of these skills makes using social media not just challenging, but potentially dangerous.

Executive Functioning Skills include:

- Good judgment

- Adequate impulse control, self-control

- Ability to shift thinking, adjust plans

- Ability to see another’s perspective

- Ability to experience the passage of time, estimate time, manage time

- Ability to self-monitor, self-regulate, and manage emotions

Social Functioning Skills include:

- Effective communication skills

- Effective ability to read non-verbal cues

- Empathy

- Listening skills, paying attention, understanding, and showing the speaker they are heard

- Emotional regulation

- Ability to resolve conflict

- Cooperation and teamwork

- Assertiveness by clearly stating needs, wants, and rights without aggression or passivity

- Social awareness including understanding and following unwritten social rules and customs (e.g., don’t pick your nose in public, etc.)

Consider the scenario where the individual with PWS receives a communication requesting a photo of their private parts in exchange for friendship. The strong desire for friendship coupled with a lack of judgement and impulse control may become problematic. If the individual with PWS is age 18 or over and the other party is a minor, we are now in some serious legal territory.

Or consider the individual with PWS who interprets a conversation benignly when in fact, the other is engaging in bullying behavior. Without ability to see things from another’s perspective and without ability to resolve conflicts effectively and amicably, there could be seriously hurt feelings, or worse. On the other hand, I’ve seen individuals with PWS brutally bully others, engaging in manipulative or intimidating behavior in attempt to achieve food, objects, relationship, or perceived higher social status.

We know from PWS specialists Janice Forster, M.D. and Linda Gourash, M.D. that core features of PWS include cognitive rigidity and an excessive drive for reward, not just for food. Because the brain’s “brakes” don’t work properly, the brain’s pleasure center tend to run on overdrive. “Enough” is never enough whether it’s food, talking, asking questions, dispensing soaps, using toilet paper, electronics time, collecting things – including collecting “Friends” on Facebook by admitting everyone without discernment. I can’t tell you how many sexually provocative photos of “Friends” on Facebook I’ve deleted from my son’s account over the years.

For many with PWS, if it was seen, read, or heard on social media, then it must be true. Often, no amount of rational argument will persuade a change of mind. This cognitive inflexibility, coupled with the need for things to be the way the individual wants them to be, not as they are, plus a degree of gullibility, naivete, and inability to see things from another’s perspective can lead to inability to accurately assess hostile, risky, or dangerous intent or consequences.

So how do we as parents and care providers help our loved one safely access social media?

First, we need to understand that our loved one needs support in order to use social media safely. Higher IQ has little impact upon managing oneself more safely. We need to provide supports for social media and smart phone use in much the same ways we provide supports in general.

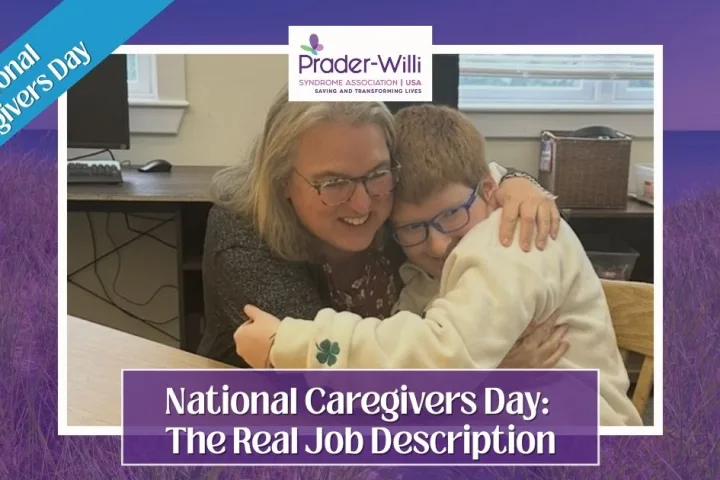

- Provide supervision at all times, the same way we do with food. We restrict our son’s access to electronics to when we are in the same room, and we have also learned (the hard way!) to position him in front of us so that we can see his screen, lest he wander to unauthorized sites.

- Regularly review all social media platforms by checking history, communications, etc.

- Use Parental Controls on all Internet-connected devices and social media platforms.

- Place limits – boundaries – around how much time may be spent on electronic devices. Remember to use Preferred Choices when determining time limits: “Let’s establish some time limits. Do you want to use Insta for 20 minutes or 25 minutes today/each day?”

Of course, there are countless additional ways to help individuals with PWS safely and responsibly access social media. We’d love to hear what you do!

Share this!

Perry A. Zirkel has written more than 1,500 publications on various aspects of school law, with an emphasis on legal issues in special education. He writes a regular column for NAESP’s Principal magazine and NASP’s Communiqué newsletter, and he did so previously for Phi Delta Kappan and Teaching Exceptional Children.

Perry A. Zirkel has written more than 1,500 publications on various aspects of school law, with an emphasis on legal issues in special education. He writes a regular column for NAESP’s Principal magazine and NASP’s Communiqué newsletter, and he did so previously for Phi Delta Kappan and Teaching Exceptional Children. Jennifer Bolander has been serving as a Special Education Specialist for PWSA (USA) since October of 2015. She is a graduate of John Carroll University and lives in Ohio with her husband Brad and daughters Kate (17), and Sophia (13) who was born with PWS.

Jennifer Bolander has been serving as a Special Education Specialist for PWSA (USA) since October of 2015. She is a graduate of John Carroll University and lives in Ohio with her husband Brad and daughters Kate (17), and Sophia (13) who was born with PWS. Dr. Amy McTighe is the PWS Program Manager and Inpatient Teacher at the Center for Prader-Willi Syndrome at the Children’s Institute of Pittsburgh. She graduated from Duquesne University receiving her Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Education with a focus on elementary education, special education, and language arts.

Dr. Amy McTighe is the PWS Program Manager and Inpatient Teacher at the Center for Prader-Willi Syndrome at the Children’s Institute of Pittsburgh. She graduated from Duquesne University receiving her Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Education with a focus on elementary education, special education, and language arts. Evan has worked with the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (USA) since 2007 primarily as a Crisis Intervention and Family Support Counselor. Evans works with parents and schools to foster strong collaborative relationships and appropriate educational environments for students with PWS.

Evan has worked with the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (USA) since 2007 primarily as a Crisis Intervention and Family Support Counselor. Evans works with parents and schools to foster strong collaborative relationships and appropriate educational environments for students with PWS. Staci Zimmerman works for Prader-Willi Syndrome Association of Colorado as an Individualized Education Program (IEP) consultant. Staci collaborates with the PWS multi-disciplinary clinic at the Children’s Hospital in Denver supporting families and school districts around the United States with their child’s Individual Educational Plan.

Staci Zimmerman works for Prader-Willi Syndrome Association of Colorado as an Individualized Education Program (IEP) consultant. Staci collaborates with the PWS multi-disciplinary clinic at the Children’s Hospital in Denver supporting families and school districts around the United States with their child’s Individual Educational Plan. Founded in 2001, SDLC is a non-profit legal services organization dedicated to protecting and advancing the legal rights of people with disabilities throughout the South. It partners with the Southern Poverty Law Center, Protection and Advocacy (P&A) programs, Legal Services Corporations (LSC) and disability organizations on major, systemic disability rights issues involving the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the federal Medicaid Act. Recently in November 2014, Jim retired.

Founded in 2001, SDLC is a non-profit legal services organization dedicated to protecting and advancing the legal rights of people with disabilities throughout the South. It partners with the Southern Poverty Law Center, Protection and Advocacy (P&A) programs, Legal Services Corporations (LSC) and disability organizations on major, systemic disability rights issues involving the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the federal Medicaid Act. Recently in November 2014, Jim retired.